“Here is a land where life is written in water.” — Thomas Hornsby Ferril, Colorado Poet Laureate

Colorado Supreme Court Justice Gregory Hobbs Jr. was a respected authority on Colorado water law, and his recent death represents a great loss to Colorado, the state’s water community in particular. Justice Hobbs was also an excellent writer, a poet, actually, and Coloradans are fortunate to have his writings about the state’s unique system of water allocation. In the “Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Law,” Justice Hobbs describes the history of the framework for using and managing Colorado water.

As Hobbs notes in the “Citizen’s Guide,” Colorado’s system of water allocation and management began to take shape 170 years ago when the first settlers arrived from New Mexico, bringing their Spanish tradition of community irrigation ditches, or acequias. The oldest continuous water right in Colorado, the 1852 People’s Ditch of San Luis, dates to this period.

In 1858, gold-seekers swarmed into the region, and mining operations were some of the first to claim water, loosely following an appropriation system established during the California gold rush. Most mining operations were short-lived, but the miners helped establish Colorado’s system of water rights.

Early settlers found good farmland in the Lower Arkansas Valley and diverted water from the Arkansas River into the Rocky Ford High Line Canal to irrigate their crops. The canal has an 1861 water right.

After Congress created the Colorado Territory in 1861, federal court rulings established a water law framework different from the Riparian Doctrine of Eastern states, which provides a water right to anyone who owns land adjacent to a body of water.

The 1862 Homestead Act and 1866 Mining Act allowed Colorado settlers to build ditches and reservoirs to divert water from public land to locations where it was needed for mining and agriculture. Otherwise, Congress allowed Western territories and states to create water law through legislation and court rulings.

In “Chaffee County: Our Water Story,” Kay Marnon Danielson describes early settlers in the Upper Arkansas Valley as predominantly farmers and ranchers. With a growing season of about five months a year, farming in the valley was limited, but large tracts of government land provided opportunities for grazing cattle.

Cattle require winter feed, so alfalfa became, and still is, a major crop. Cattle and food crops were raised to feed growing Front Range cities in addition to the boomtowns in mountain mining districts. These Upper Ark Basin agricultural activities required water, which required irrigation ditches like the Trout Creek Ditch, the oldest ditch in Chaffee County with an 1864 appropriation date.

Adopted in 1876, the Colorado Constitution formalized the Prior Appropriation System as the basis for state water law. Under Prior Appropriation, water users with earlier water right decrees hold a “senior” right and can take water to meet their needs before holders of more recent or “junior” rights.

As an example, the Rocky Ford High Line Canal’s 1861 appropriation date gives it priority over the Trout Creek Ditch’s 1864 water right. So, in a dry year water diversions for the Trout Creek Ditch can be curtailed to ensure that the High Line Canal receives its water (because the High Line has the older water right, i.e., the earlier appropriation date).

In 1882, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that, under the Prior Appropriation System, water can be appropriated in one watershed and imported to a different watershed to be put to beneficial use (Coffin v. Left Hand Ditch Co.).

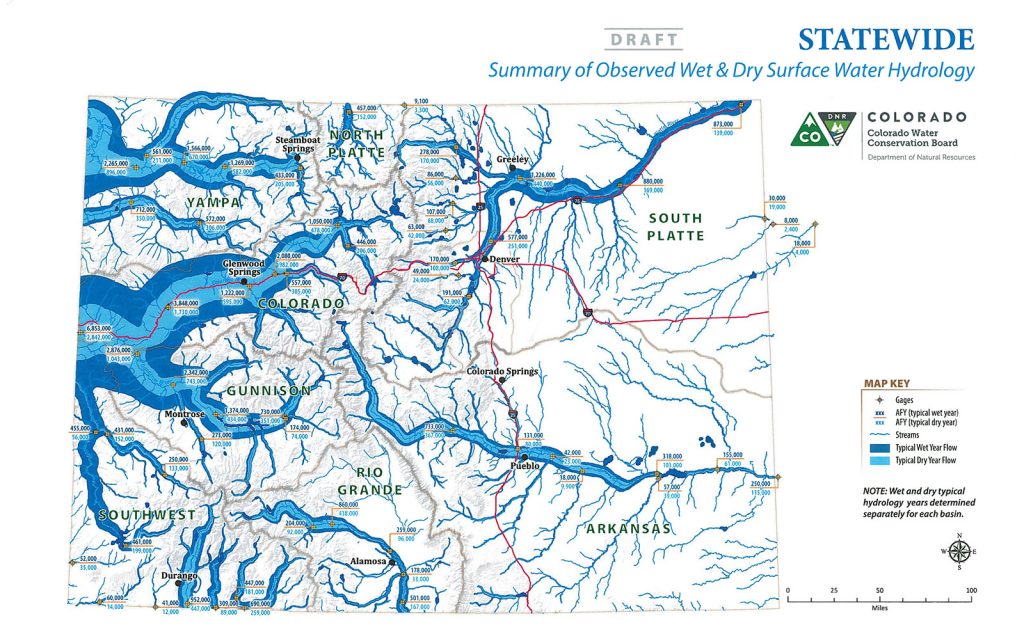

Since 80% of Colorado’s water occurs west of the Continental Divide and 90% of the state’s population resides east of the Divide, planners and water managers have historically looked to the West Slope watersheds to support Front Range agriculture and population centers. As a result, “24 tunnels and ditches move 500,000 acre-feet of water from west to east each year.”

The Arkansas River Basin is no exception. It has the largest land mass of Colorado’s river basins, but it yields one of the smallest quantities of native water, contributing to its status as the most over-appropriated basin in the state.

Limited quantities of native water have also prompted “trans-basin diversions,” which bring an average of 130,000 acre-feet of water per year from the Colorado River Basin into the Arkansas River Basin – nearly 15% of the Ark Basin’s water supply, as calculated by the Colorado Division of Water Resources.

The Prior Appropriation System provides a process by which water users can obtain a court decree for their water rights. That process, called adjudication, sets:

- The date of the water right.

- The source of the water.

- The point from which that water is diverted.

- The type of beneficial use.

- The place where the water is used.

To legally appropriate water in Colorado, the water user must put the water to a “beneficial use,” which requires a plan to divert and/or store the water for a legally recognized beneficial use. Colorado water law defines beneficial use as a lawful “appropriation” of water employing efficient practices to use the water without waste.

According to Justice Hobbs, the goal is to avoid waste so that as much water as possible is available to as many right holders as possible.

Water uses recognized as “beneficial” have expanded through the years and include, among others: agricultural irrigation, municipal uses, commercial uses, domestic uses, industrial uses, recreational uses and snowmaking. In-stream flows were legally recognized as a beneficial use in 1979. Since then, the Colorado Water Conservation Board has claimed in-stream flow water rights for thousands of miles of Colorado waterways, but those rights remain junior to most other water rights.

For more than 125 years now, the Colorado Division of Water Resources has fulfilled the responsibility of administering the Prior Appropriation System. Directed by the State Engineer, this work is carried out through the Division Offices – one for each of the Colorado’s seven major river basins – each led by a Division Engineer. The Arkansas River Basin is administered by Division 2.

Water Commissioners, who report to the Division Engineers, are the boots on the ground working to enforce Water Court decrees and state water law.

“Written in Water” is a series of articles exploring Colorado’s most precious natural resource.